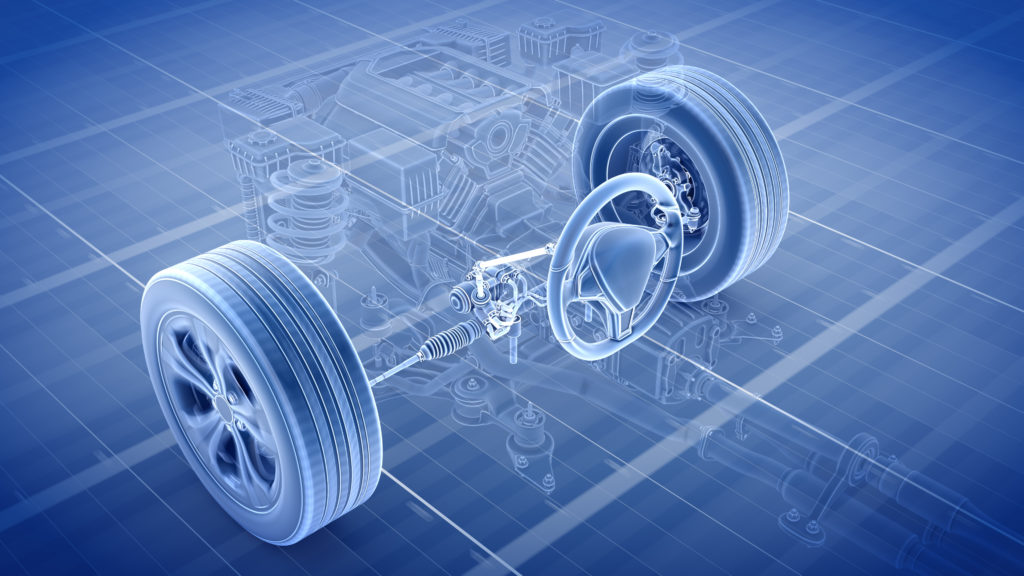

In very simple terms, a car is a body of weight (the chassis) suspended on four springs, one at each corner (the suspension), with a tyre connecting the car with the ground under each of those four springs. When it is stood still, you can have a perfectly balanced platform with the weight spread equally between each of the four corners, pushing the tyres into the ground by an equal amount.

Weight Balance and Transference

However, as soon as you start to drive, the weight of the car will begin to move around on the springs and fundamentally alter that balance. For example, when we accelerate, the weight of the car will shift towards the rear, so if you could weigh the car at that point, you would see that while the overall weight is the same, it will now be heavier at the rear than it was before, and conversely lighter at the front. Think of a motorbike pulling a wheelie. The weight has shifted dramatically to the rear!

The tyres rely on being pushed into the ground in order to create grip. Within reason, the more you press the tyre into the road, the more grip it has, but if you reduce that downward pressure, you also reduce grip.

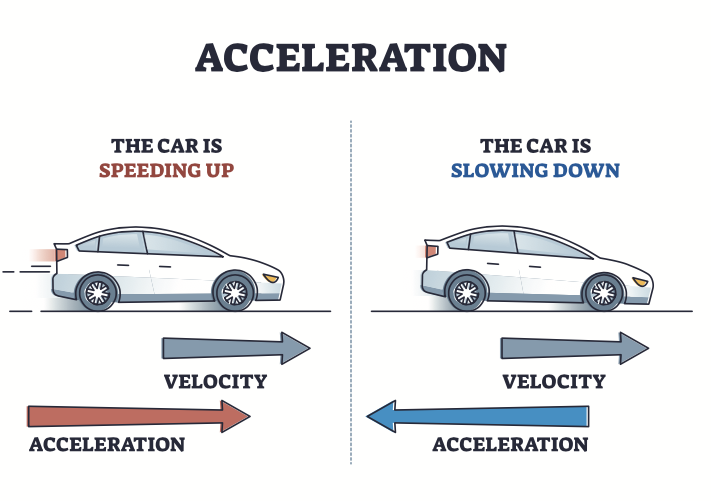

Acceleration and Braking

If we now go back and look at our accelerating car, we can start to understand how weight movement directly affects the tyres and changes where you have grip and how much you have at each end of the car. Understanding that can be extremely useful and is a fundamental part of a racing driver’s art.

With our accelerating car, we have shifted the weight more onto the rear wheels and squashed them more into the road, very useful if the car is rear-wheel drive! When we brake, clearly the opposite happens, and the weight will shift to the front, creating extra grip on the front wheels but reducing it at the rear.

With both of these scenarios, we are only shifting the weight around in line with the direction of travel, so the imbalance of grip front to rear doesn’t really upset anything else. We are not fighting against the forces acting on the car but working in the same direction as them. Because of that the overall platform remains pretty stable.

During our advanced driving courses, we teach you about intelligent use of tyre grip not only from a technical viewpoint but also tyres from a safety perspective. At the start of each course, we do comprehensive safety checks, which include your tyres.

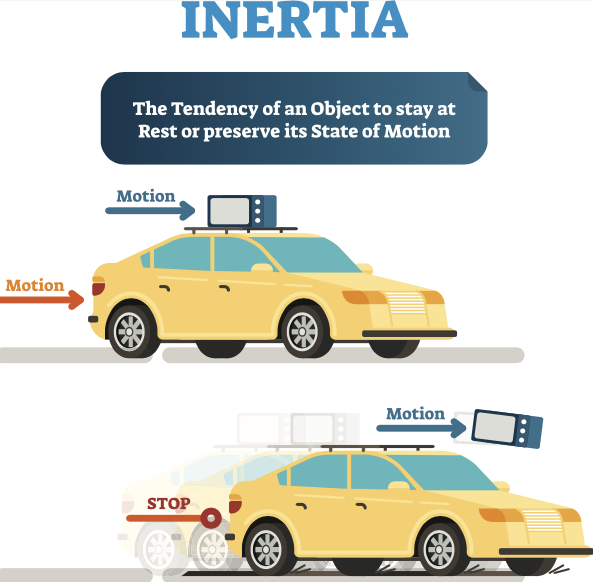

The difficulty comes when we introduce steering inputs. Going around corners is actually quite a hard thing for a car to physically do, as it is working against a very powerful force – inertia.

Working With Inertia

Inertia dictates that a body of weight that is moving really wants to just carry on in a straight line. When you turn the steering wheel, the tyres will try to force the car to deviate from going straight, something that the force of inertia will resist.

If you suddenly removed the grip, the car would instantaneously follow the forces acting on it and go straight on. It takes a lot of energy for the tyres to overcome this phenomenon.

When we steer, the weight of the car has shifted over to one side, toward the outside of the corner, so if you’re turning right, the left-hand side tyres will have more grip. We now have an imbalance that is not in line with the direction of travel.

Steering then creates an instability that is much more precarious than braking or accelerating and needs more careful management from the driver.

Let’s delve a little deeper and look at what happens as we approach and travel through a corner.

Steering the Corner

As we have seen, while we are running in a straight line, we can brake pretty much as hard as we like without upsetting the car too much. As we approach the point at which we need to begin steering, we should be gradually reducing the brake pressure and allowing the weight to settle back to a more neutral balance of fairly equal levels of grip front to rear.

This is very important as we know that once we start to steer and work against the forces of inertia, we will be unbalancing the car side to side as well. If we have too much brake applied and there is not enough weight pushing down on the rear tyres, introducing the steering could cause the rear tyres to begin to slide as they don’t have enough grip to cope. If we release the brakes too quickly, the front of the car may actually go a little light and reduce the ability to turn fractionally. Smooth operation is vital.

The same is true when we turn the steering wheel. We don’t want to make the car jump; we want to build the cornering forces progressively so that the tyres have time to build up grip. It also means that the weight shift happens more slowly and doesn’t build any moment itself, which can cause further issues!

Once the car begins to change direction, the sheer effort that it takes for the tyres to make it happen will create a lot of scrub, which will slow the car down. It is, in effect, a form of braking so the weight of the car will begin to shift forwards again, altering the balance. To counteract that, we now need to gently apply a small amount of throttle. What you are looking for is just enough power to maintain the speed we have, not accelerating, just holding still. That will keep the chassis balanced front to rear and keep the platform as stable as possible at the most vulnerable time.

Accelerating Away

The cue to begin actually accelerating is when you start to unwind the steering wheel. Any sooner and you will upset the delicate equilibrium we have created. Imagine doing a wheelie in the middle of a corner! As we reduce the cornering loads by straightening the steering, we can gradually increase the throttle at the same rate so that we are not upsetting the balance of grip.

The principles apply wherever you are, so if you are driving as quickly as you can on a racing circuit or trying to be as smooth and progressive as possible on the road, they are the same, albeit applied differently. As drivers, we need to work with our cars and coax them to do things, not force or bully them. While the information above can be very relevant to track driving, it’s also highly relevant to road driving too. As mentioned previously, a good driver needs to be smooth and balanced. Forward planning and observation – two key elements we teach on our on-road courses help a driver be both of these. If you’re observing and planning you will be much less likely to make rushed, unplanning movements. This is all part of the System of Car Control – a systematic method taught by Police drivers as part of their advanced driver training.

If you wish to become a safer, more skilful driver, please contact us. We have full UK coverage and provide training for both business and private clients.